4. Logic

4.1. Propositional Logic

A proposition is a sentence that declares a fact that is either True or False.

Propositional logic consists of a set of formal rules for combining propositions in order to derive new propositions.

In Python, we can use boolean variables (typically \(p\) and \(q\)) to represent propositions and define functions for each propositional rule. Each rule can be implemented using the boolean operators (and, or, not) discussed in the section on operators and expressions .

A truth table is a method of showing truth values of compound propositions using the truth values of its components. It is typically created with rows representing possible truth values and columns representing the propositions.

4.1.1. Negation

The negation is a statement that has the opposite truth value. The negation of a proposition \(p\), denoted by \(\neg p\), is the proposition "It is not the case , that \(p\)".

For example, the negation of the proposition "Today is Friday." would be "It is not the case that, today is Friday." or more succinctly "Today is not Friday."

| \(p\) | \(\neg p\) |

|---|---|

|

True |

False |

|

False |

True |

4.1.2. Conjunction

"I am a rock and I am an island."

Let \(p\) and \(q\) be propositions. The conjunction of \(p\) and \(q\), denoted in mathematics by \(p \land q\), is True when both \(p\) and \(q\) are True, False otherwise.

| \(p\) | \(q\) | \(p \land q\) |

|---|---|---|

|

True |

True |

True |

|

True |

False |

False |

|

False |

True |

False |

|

False |

False |

False |

4.1.3. Disjunction

"She studied hard or she is extremely bright."

Let \(p\) and \(q\) be propositions. The disjunction of \(p\) and \(q\), denoted in mathematics by \(p \lor q\), is True when at least one of \(p\) and \(q\) are True, False otherwise.

| \(p\) | \(q\) | \(p \lor q\) |

|---|---|---|

|

True |

True |

True |

|

True |

False |

True |

|

False |

True |

True |

|

False |

False |

False |

4.1.4. Exclusive Disjunction

"Take either 2 Advil or 2 Tylenol."

Let \(p\) and \(q\) be propositions. The exclusive disjunction of \(p\) and \(q\) (also known as xor ), denoted in mathematics by \(p \oplus q\), is True when exactly one of \(p\) and \(q\) are True, False otherwise.

| \(p\) | \(q\) | \(p \oplus q\) |

|---|---|---|

|

True |

True |

False |

|

True |

False |

True |

|

False |

True |

True |

|

False |

False |

False |

|

Exclusive disjunction can be thought of as one or the other, but not both. |

4.1.5. Implication

" If you get a 100 on the final exam, then you earn an A in the class."

Let \(p\) and \(q\) be propositions. The implication of \(p\) and \(q\), denoted in mathematics by \(p \implies q\), is short hand for the statement "if p then q". As such, implication requires \(q\) to be True whenever \(p\) is True. If \(p\) is not True, then \(q\) can be any value. In other words, implication fails (is False) when \(p\) is True and \(q\) is False. Note, this is different from "p if and only if q".

| \(p\) | \(q\) | \(p \implies q\) |

|---|---|---|

|

True |

True |

True |

|

True |

False |

False |

|

False |

True |

True |

|

False |

False |

True |

|

Implication can be considered a "contract" which fails only when the conditions are met and the results are not fulfilled. |

4.1.6. Converse, Contrapositive and Inverse of an Implication

We can form new compound propositions from the implication, \(p \implies q\). They are

-

The converse : \(q \implies p\)

-

The contrapositive : \( \neg q \implies \neg p\)

-

The inverse \( \neg p \implies \neg q\)

The truth tables for these new propositions are shown in the table.

| \(p\) | \(q\) | \(p \implies q\) (conditional) | \(q \implies p \) (converse) | \( \neg q \implies \neg p\) (contrapositive) | \( \neg p \implies \neg q\) (inverse) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

True |

True |

True |

True |

True |

True |

|

True |

False |

False |

True |

False |

True |

|

False |

True |

True |

False |

True |

False |

|

False |

False |

True |

True |

True |

True |

In the section proposition equivalences we will explain why the truth table shows that the conditional \(p \implies q\) and contrapositive \( \neg q \implies \neg p\) are logically equivalent, and why the converse \(q \implies p\) and inverse \( \neg p \implies \neg q\) are logically equivalent.

We illustrate these ideas with an example.

4.1.7. Bi-Implication

"It is raining outside if and only if it is a cloudy day."

Let \(p\) and \(q\) be propositions. The bi-implication of \(p\) and \(q\), denoted in mathematics by \(p \iff q\), is short hand for the statement "p if and only if q". As such, bi-implication requires \(q\) to be True only when \(p\) is True. In other words, bi-implication fails (is False) when \(p\) is True and \(q\) is False or when \(p\) is False and \(q\) is True.

| \(p\) | \(q\) | \(p \iff q\) |

|---|---|---|

|

True |

True |

True |

|

True |

False |

False |

|

False |

True |

False |

|

False |

False |

True |

|

Bi-implication is True if the propositions have the same truth value and False otherwise. |

It is important to contrast implication with bi-implication. Consider the implication example "If you get a 100 on the final exam, then you earn an A in the class." This means that when you get a 100 on the final you also get an A in the class.

As a bi-implication it would say "You get a 100 on the final exam if and only if you earn an A in the class." This becomes a two-way contract where you can earn an A in the class by getting a 100 on the final, but if you do not get a 100 on the final you will not earn an A.

4.1.8. Compound Propositions

To find truth values of compound propositions, it is useful to break them up into smaller parts.

When creating your own truth table it is crucial to be systematic about ensuring you have all possible truth values for each of the simple propositions. Each simple proposition has two possible truth values, so the number of rows in the table should be \(2^n\) where \(n\) is the number of propositions. You should also consider breaking complex propositions into smaller pieces.

Logical Translations

A long time ago philosophers discovered we could put our thoughts into symbols and more easily follow lines of reasoning. This was an important step in the eventual development of our modern technological society and our use of digital computers. Before computers can work, we have to put our thoughts into them.

BUT, the English language is difficult and we use many different phrases to represent the same logical statements. Translating statements from English sentences to symbols and back is a skill that needs lots of practice.

4.2. Proposition Equivalences

Two propositions are considered logically equivalent (or simply equivalent ) if they have the same truth values in every instance. It is often easiest to see this by constructing a truth table for the two propositions and comparing.

4.2.1. De Morgan’s Laws

Two important logical equivalences are De Morgan’s Law. These describe how we "distribute" the negation across the and and or operators.

| We use the symbol \(\equiv\) to denote two statements which are logically equivalent. |

4.2.2. Tautologies, Contradictions and Contingencies

A proposition is a tautology if its truth value is always True.

A proposition is a contradiction if its truth value is always False.

A proposition that is neither a tautology nor a contradiction is said to be a contingency .

4.3. Predicates and Quantifiers

4.3.1. Predicates

A predicate is a statement involving a variable.

Predicates are denoted as \(P(x)\) or \(Q(x,y)\) where \(P\) and \(Q\) represent the statements and \(x\) and \(y\) represent the possible values. After a value is assigned to each variable, the predicate becomes a proposition which has a truth value.

4.3.2. Quantifiers

Consider the statements

-

For all integers \(x\), \(x^2\geq 0\).

-

Some student in the class has a birthday in July.

Each of these statements considers a proposition over an entire population or set, called the domain, and quantifies how many elements (or people) in the set satisfy the proposition. To represent this idea, we use two main quantifiers, the universal quantifier and the existential quantifier .

The Universal Quantifier , \(\forall\), represents the statement "for all", "for every", "for each". When it comes before a statement, it means that statement is true for all values in the domain.

The Existential Quantifier , \(\exists\), represents the statement "there exists", "for some", "at least one". When it comes before a statement, it means the statement is true for at least one value in the domain.

Recall the previous example statements:

-

For all integers \(x\), \(x^2 \geq 0\).

Let \(P(x)\) be the predicate "\(x^2 \geq 0\)". Then we write the statement as \(\forall x P(x)\), where the domain is the set of all integers. This quantified statement will be true since anytime you square a nonzero integer it is positive and \(0^2=0\).

-

Some student in the class has a birthday in July.

Let \(Q(s)\) be the predicate "student \(s\) has a birthday in July". Then we write the statement as \(\exists s Q(s)\), where the domain is the set of all students in the class. This statement will be true as long as at least one student in the class has a birthday in July. It will be false, otherwise.

4.3.3. Negation of Quantifiers

It is important to consider the negation of a quantified expression.

-

"Every student in this class has taken Programming Fundamentals."

This is a universally quantified statement and can be expressed as \(\forall x P(x)\) where \(P(x)\) is the statement "\(x\) has taken Programming Fundamentals" and the domain consists of all the students in this class. The negation of the statement would be "It is not true that every student in this has taken Programming Fundamentals." Equivalently,

-

"There is a student in this class who has NOT taken Programming Fundamentals."

This is an existentially quantified statement expressed as \(\exists x \neg P(x)\).

This demonstrates that the negation of a universally quantified statement is an existential statement. In symbols, we have \(\neg \forall x P(x)\equiv \exists x \neg P(x)\).

Similarly, the negation of an existential statement is a universal statement. \(\neg \exists x P(x) \equiv \forall x \neg P(x)\).

The predicate of a quantified statement could be a compound statement. For instance,

-

Some dogs are big and fluffy.

This is written as \(\exists x (B(x) \land F(x))\) where \(B(x)\) is the proposition "\(x\) is big." and \(F(x)\) is the proposition "\(x\) is fluffy." and the domain is dogs. Negating this statement would give

\(\neg \exists x (B(x) \land F(x)) \equiv \forall x \neg (B(x) \land F(x)) \equiv \forall x (\neg B(x) \lor \neg F(x))\)

In words,

-

All dogs are not big or not fluffy.

4.3.4. Nested Quantifiers

There are times it will take more than one quantifier to express a statement.

-

For all integers \(x\), there exists an integer \(y\), such that \(x+y=0\).

This statement contains both a universal and an existential quantifier. \(\forall x \exists y S(x,y)\) where \(x\) and \(y\) are integers and \(S(x,y)\) is the proposition \(x+y=0\). This statement means, if you have any integer \(x\) (for instance \(x=5\)) then you can find an integer \(y\) (for instance \(y=-5\)) such that \(x+y=0\).

The order of the quantifiers matters. \(\exists x \forall y S(x,y)\) would be

-

There exists an integer \(x\), such that for all integers \(y\), \(x+y=0\).

Note that in this statement you find an integer \(x\) so that when you add any integer \(y\) to it you always get 0.

The first statement, for all integers \(x\), there exists an integer \(y\) such that \(x+y=0\), is true. For any integer \(x\) you could choose \(y=-x\) and \(x+y=x+(-x)=0\). While the second statement, there exists an integer \(x\), such that for all integers \(y\), \(x+y=0\), is false.

To negate nested quantifiers, repeatedly apply De Morgan’s Laws of negating a quantifier and a predicate.

Namely, \(\neg \forall x P(x) \equiv \exists x \neg P(x)\) and \(\neg \exists x P(x) \equiv \forall x \neg P(x)\).

4.4. Applications of Logic

In this section we consider two applications of logic to information technology and computer science. The first involves bitwise operations, and the second designing and analyzing logic circuits.

4.4.1. Bitwise operations

A bitwise operation is a Boolean operation that operates on the individual bits (\(0s\), or \(1s\)) of the operand(s) and are summarized

We summarize the truth tables for the bitwise boolean operators.

| \(p\) | \(q\) | \(AND\) & | \( \ OR\ | \) | \(XOR\) \({}^{\wedge}\) | \(IF\) \(\Rightarrow\) | \(IFF\) \(\Leftrightarrow\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

4.4.2. Logic Circuits

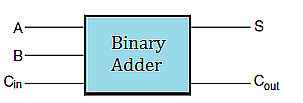

Logic circuits are important in designing the arithmetic and logic units of a computer processor. Consider the problem of adding two \(8\)-bit numbers in binary. In binary \(0+0=0\), and \(1+0=0+1=1\), but, as in decimal addition, in binary \(1+1=2\), which in binary will be a sum of \(0\) and a carry of \(1\) to the next significant column on the left. Thinking then of adding a specific column of two binary digits, say \(A\) and \(B\), involves as input the digits \(A, B\) and the carry in from the previous column say \(C_{in}\). The output will be the sum \(S\) and the carry out to the next column, say \(C_{out}\). These are the basic components of what is called a binary adder.

The logic table for binary addition based on the digital inputs \(A, B, C_{in}\), and digital outputs \(S\) and \(C_{out}\) is summarized in the table.

| \(A\) | \(B\) | \(C_{in}\) | \(\mathbf{S}\) | \(\mathbf{C_{out}}\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

\(\mathbf{1}\) |

\(\mathbf{1}\) |

|

1 |

1 |

0 |

\(\mathbf{0}\) |

\(\mathbf{1}\) |

|

1 |

0 |

1 |

\(\mathbf{0}\) |

\(\mathbf{1}\) |

|

1 |

0 |

0 |

\(\mathbf{1}\) |

\(\mathbf{0}\) |

|

0 |

1 |

1 |

\(\mathbf{0}\) |

\(\mathbf{1}\) |

|

0 |

1 |

0 |

\(\mathbf{1}\) |

\(\mathbf{0}\) |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

\(\mathbf{1}\) |

\(\mathbf{0}\) |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

\(\mathbf{0}\) |

\(\mathbf{0}\) |

It can be shown that the logic for the outputs \(S\), and \(C_{out}\) is given by the following propositions \[ C_{out}=(A\land B)\lor \left(B\land C_{in}\right)\lor \left(A\land C_{in}\right)\] \[S=\left(\sim A\land \sim B\land C_{in}\right)\lor \left(\sim A\land B\land \sim C_{in}\right)\lor \left(A\land \sim B\land \sim C_{in}\right)\lor \left(A\land B\land C_{in}\right) \]

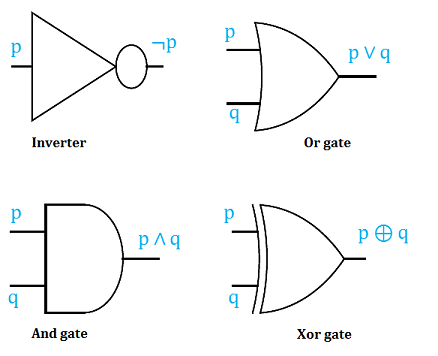

Implementing these logical outputs based on the inputs \((A,B, C_{in})\), is through the use of electronic circuits called logic gates.

The basic logic gates, are the Inverter or Not gate, the And gate, the Or gate and the Xor gate. The graphical representation for each is shown below.

We end this section by first analyzing logic circuits to give their outputs in terms of their input variables, and then, constructing logic circuits based on logical statements.

In the next two examples, we design logic circuits based on logical propositions. The idea is to work backward using order of operations from the right to the left.

4.5. Exercises

-

Which of these statements are propositions? Explain your reasoning

-

Is Atlanta the capital of Georgia?

-

All birds fly

-

\(2\ \times\ \ 3\ =\ 5\)

-

\(5\ +\ 7\ =\ 7+5\)

-

\(x\ +\ 2\ =\ 11\)

-

Answer this question.

-

The rain in Spain

-

-

Construct truth tables for,

-

\(a\vee b\Rightarrow\lnot b\)

-

\((a\vee\lnot b)\ \Leftrightarrow\ a\)

-

\((a\Rightarrow b)\ \bigwedge\ (b\ \bigwedge\ \lnot c)\)

-

\((a\ \bigvee\ b)\ \Rightarrow\ (\ \lnot c\ \bigvee\ a)\)

-

\((a\ \bigvee\ b)\ \bigwedge\ (c\ \bigvee\lnot d\ )\)

-

\((\lnot c\ \bigwedge\ \ b)\ \bigvee\ \ (a\Rightarrow\ \lnot d\ )\)

-

-

Using truth tables, determine if each of the following is a tautology, contradiction, or neither (conditional)

-

\(\neg ((a\lor b)\lor (\neg a\land \neg b))\)

-

\(\left(\left(a\vee b\right)\land\lnot a\right)\Rightarrow b\)

-

\(\left(\left(a\vee b\right)\land a\right)\Rightarrow b\)

-

\(p\land r)\lor (\neg p\land \neg r)\)

-

\(\neg ((p\lor q)\lor (\neg p\land (\neg q\lor r)))\)

-

\(\neg (p\land q)\lor (q\lor r)\)

-

-

Using truth tables determine which of the following are equivalent

-

\(\left(p\Rightarrow q\right)\Rightarrow r\),

\(\left(p\land\lnot q\right)\vee r,\) and

\(\left(p\land\lnot q\right)\land r\)

-

\((a\lor b)\land c,\)

\((c\land a)\lor (c\land b),\) and

\(\neg ((\neg a\land \neg b)\lor \neg c)\)

-

-

Let \(C(x)\) be the statement "\(x\) has visited Canada." where the domain consists of the students at GGC. Express each of the quantifications in English.

-

\(\exists x C(x)\)

-

\(\forall x C(x)\)

-

How would you determine whether each of these statements is true or false?

-

-

Determine the truth value of each of these statements if the domain for all variables, \(m , n\) is the set of all integers, \(\mathbb{Z}\), explaining your reasoning.

-

\(\forall n:\left(n^2\geq 1\right)\)

-

\(\forall n:\left(n^2\geq 0\right)\)

-

\(\ \exists\ n:(n^2=3)\)

-

\(\ \exists\ m\forall\ n:(m+n=n-m)\)

-

\(\forall\ n\exists\ m:\ (n\cdot\ m=m)\)

-

\(\ \exists\ n\forall\ m:\ (n\cdot\ m=m)\)

-

\(\ \exists\ n\forall\ m:\ (n\cdot\ m=n)\)

-

-

Consider each of the compound propositions. (i) Translate each using logical symbols and letters, stating what each letter represents, (ii) Negate each using plain English sentences, and (iii) Translate the negated statements using logical symbols and quantifiers.

-

If it snows today, then I will go skiing tomorrow.

-

Mei walks or takes the bus to class.

-

Every person in this class understands mathematical induction.

-

In every mathematics class there is some student who falls asleep during lectures.

-

There is a building on the campus of some college in the United states in which every room is painted white.

-

-

Let \(p\), be the proposition ”My bicycle needs a tire replaced,” \(q\), be the proposition ”I will go cycling”, and, \(r\), be the proposition ”Rain is in the forecast.”

-

Express each of these compound propositions using plain English sentences.

-

\(\neg p\vee q\)

-

\(\neg p\Rightarrow \neg q\)

-

\((\neg p\wedge r)\Rightarrow q\)

-

\((\neg p\wedge r)\Rightarrow q\)

-

\((\neg p\wedge q)\vee r\)

-

-

Write these compound propositions using \(p\), \(q\) and, \(r\) and logical connectives (including negation).

-

If my bicycle tire does not replacement I will go cycling.

-

My bicycle tire does not replacement, there is rain in the forecast but I will go cycling

-

Whenever there is rain in the forecast, I do not go cycling.

-

If there is rain in the forecast or my tire needs replacement I will not go cycling.

-

Rain is not forecast whenever I go cycling.

-

Rain is not forecast and my tire does not need replacement whenever I go cycling.

-

-

-

Design logic circuits with the following output

-

\((p\lor (q\land \neg r))\lor \neg (p\land q)\)

-

\((p\lor (q\land r))\land \neg (p\land q)\)

-

-

Consider the predicate \(Q(x,y): x\ \cdot\ y=5\), where the domain of \(x\) and \(y\) is all positive real numbers \(\mathbb{R}^+\), or \(x,\ y\ >0\). Determine the true value of the following, an explain your reasoning.

-

\(Q(1,5)\)

-

\(Q\left(2,\frac{5}{2}\right)\)

-

\(\exists\ y,\ Q\left(7,y\right)\)

-

\(\ \forall\ y,\ Q\left(7,y\right)\)

-

\(\exists\ x\ \forall\ y,\ Q\left(x,y\right)\)

-

\(\ \forall\ \ x\ \exists\ \ y,\ Q\left(x,y\right)\)

-

-

Consider the predicate \(R(x,y):\ 2x+y=0\), where the domain of \(x\) and \(y\) is all rational numbers, \(\mathbb{Q}\). Determine the true value of the following, an explain your reasoning.

-

\(R(0,0)\)

-

\(R(2,-1)\)

-

\(R\left(\frac{1}{5},-\frac{2}{5}\right)\)

-

\(\exists y,\ R\left(0.2,y\right)\)

-

\(\ \forall y,\ R\left(7,y\right)\)

-

\(\exists\ x\forall\ y,\ R\left(x,y\right)\)

-

\(\ \forall\ x\ \exists\ y,\ R\left(x,y\right)\)

-

-

Calculate the bitwise \(AND\), the bitwise \(OR\), and the bitwise \(XOR\) of the following pairs of bytes, or sequence of bytes

-

\(01111111\) and \(11101001\)

-

\(1110010111111010\) and \(0101110101100011\)

-

-

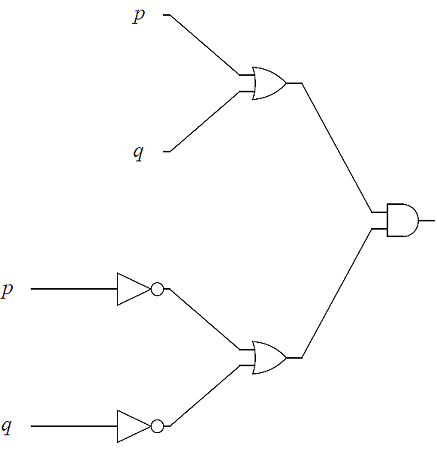

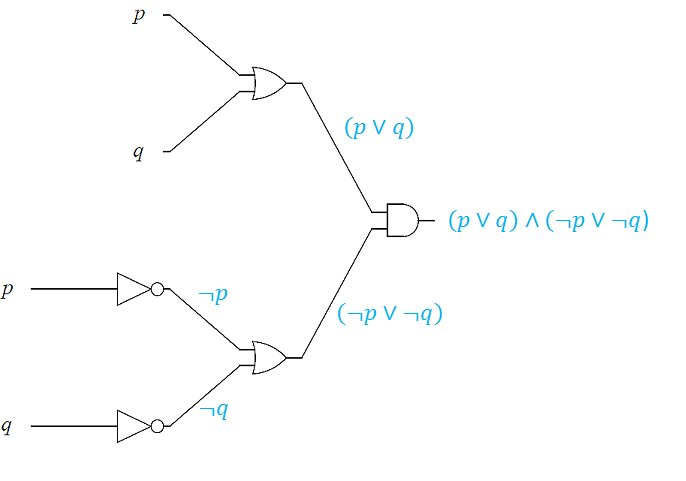

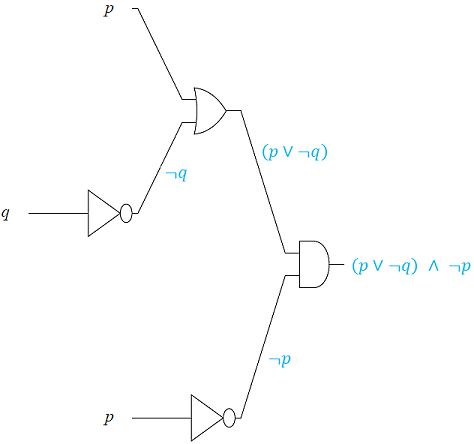

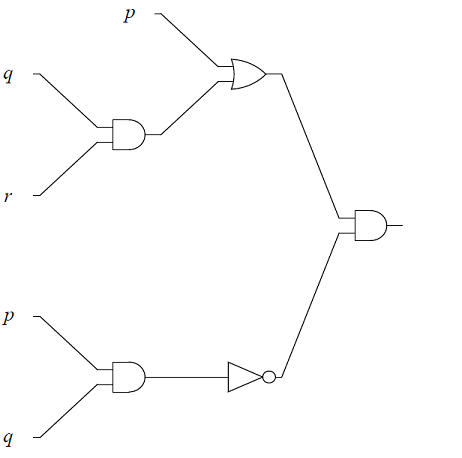

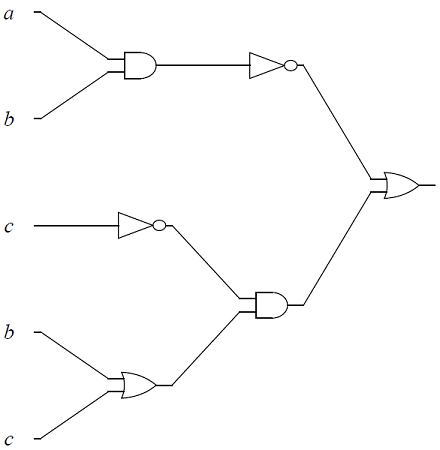

Give the output for each of the logic circuits in terms of the input variables,

-

The logic circuit, with input variables, \(p, q\), \(r\).

-

The logic circuit, with input variables, \(a, b\), \(c\).

-

-

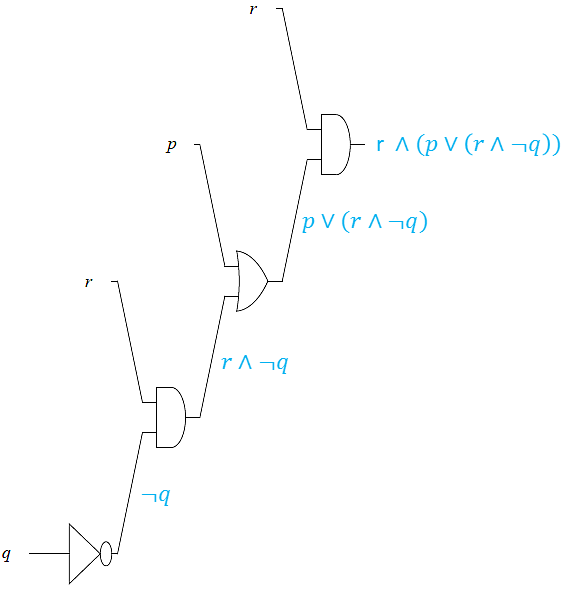

Design a logic circuit for \(r\land (p\lor (r\land \neg q))\).