13. Appendix 1: Library of Functions

Functions can in many cases be visualized graphically, for example when mapping from the real line, \(\mathbb{R}\) to the real line, such maps are viewed on a Cartesian plan.

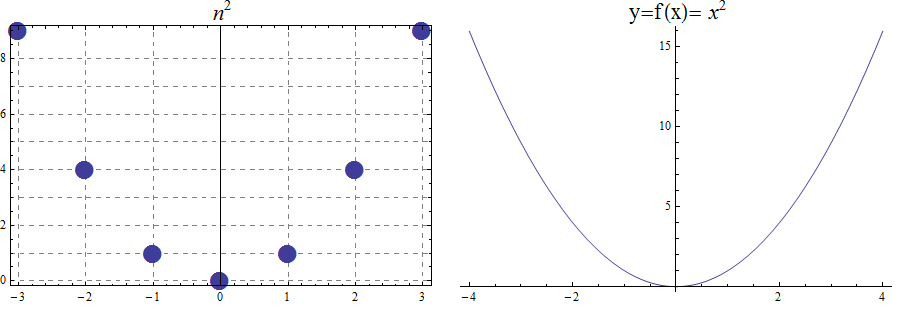

13.1. Quadratic Function

The function \(f(x) =x^2\), denotes the association \((a,b) =(x, x^2)\) with \(f : \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\). We notice that the range is the set of real numbers \([0, \infty)= \mathbb{R}^{+}\). The function is not invertible, since it is not injective. For example, we have both \(f(-3) =9\) and \(f(3)=9\). With \(f : \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}\) notice that the range is now \(\mathbb{N}\)

\begin{array}{lccccccccccc} & x & -5 & -4 & -3 & -2 & -1 & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ & x^2 & 25 & 16 & 9 & 4 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 4 & 9 & 16 & 25 \end{array}

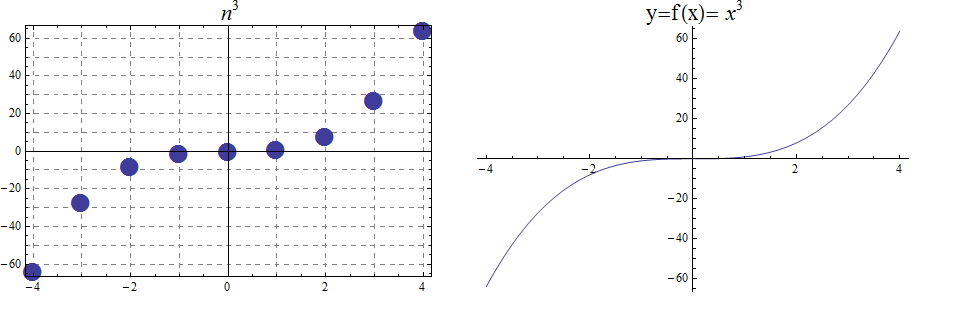

13.2. The Cubic function

The function \(f(x) =x^3\), denotes the association \((a,b) =(x, x^3)\) with \(f : \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\). Also, we notice that the range is the set of all real numbers \((- \infty , \infty)=\mathbb{R}\). The function is bijective and so invertible. With \(f : \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}\), notice that the range, in addition to domain, is also \(\mathbb{Z}\)

\begin{array}{llcccccccccl} & x & -5 & -4 & -3 & -2 & -1 & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ & x^3 & -125 & -64 & -27 & -8 & -1 & 0 & 1 & 8 & 27 & 64 & 125 \end{array}

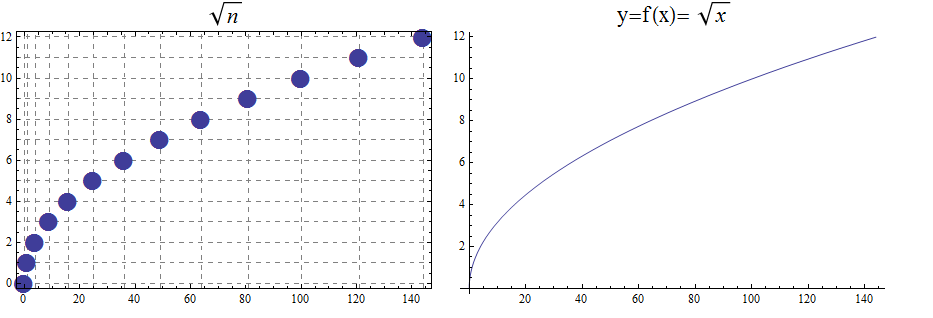

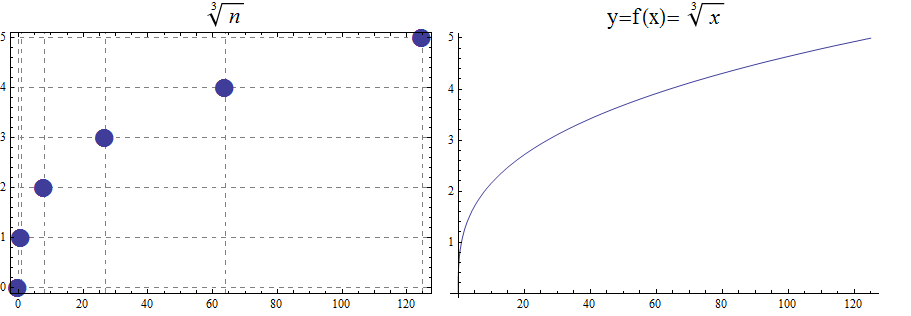

13.3. The Square Root and Cube Root Functions

For the purposes of completeness and for comparing how fast functions \(f(x)\) grow for large x, we present the inverse of the functions \(f(x)= x^2\) and \(f(x)= x^3\), when \(f(x):\mathbb{R}+→\mathbb{R}+\). Respectively, the functions\( f(x)=\sqrt{x}\) and \(f(x)= \) \$root(3)(x)\$.

\begin{array}{lcccccccccclll} & x & 0 & 1 & 4 & 9 & 16 & 25 & 36 & 49 & 64 & 81 & 100 & 121 & 144 \\ & \sqrt{x} & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 & 8 & 9 & 10 & 11 & 12 \end{array}

\begin{array}{lcccccl} & x & 0 & 1 & 8 & 27 & 64 & 125 \\ & \sqrt[3]{x} & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \end{array}

13.4. Exponential and Logarithmic Functions

We begin by summarizing important properties of exponentials.

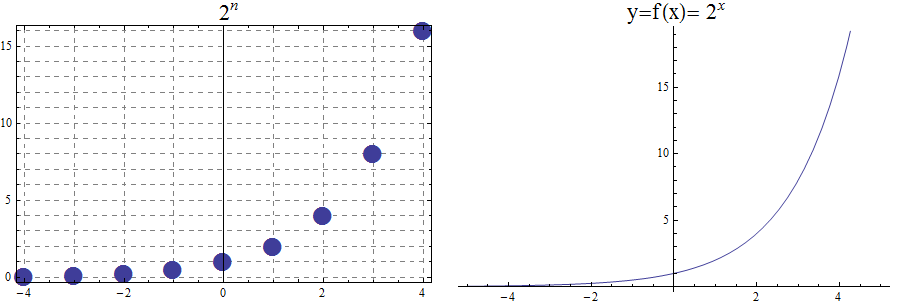

13.4.1. Exponential Functions

Exponential functions are of the form \(f\left(x\right)=b^x\), where \(b\) is the base and the variable \(x\) is in the exponent. The base \(b>0\) and \(b ≠ 1\). Properties of exponential functions come from properties of exponents. When the base \(b\) is greater than 1 the exponential function is increasing exponentially, as in the case \(f(x) = 2^x\).

\begin{array}{llcccccccccl} & x & -5 & -4 & -3 & -2 & -1 & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ & 2^x & \frac{1}{32} & \frac{1}{16} & \frac{1}{8} & \frac{1}{4} & \frac{1}{2} & 1 & 2 & 4 & 8 & 16 & 32 \end{array}

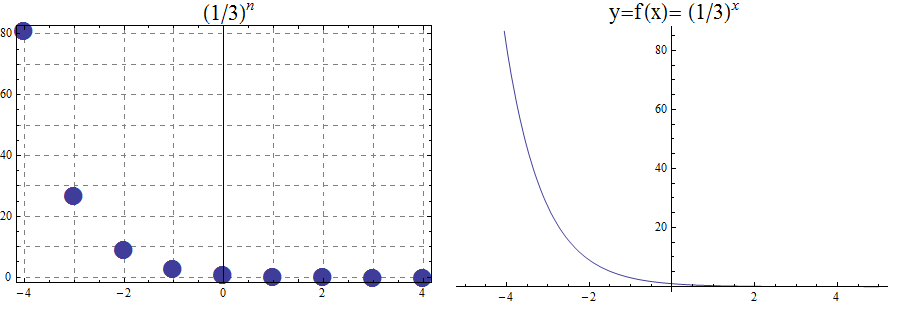

When the base \(b\) is less than 1 the exponential function is decreasing exponentially, as in the case \(f(x) = \left(\frac{1}{3}\right) ^x\).

\begin{array}{llcccccccccl} & x & -5 & -4 & -3 & -2 & -1 & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ & (\frac{1}{3})^x & 243 & 81 & 27 & 9 & 3 & 1 & \frac{1}{3} & \frac{1}{9} & \frac{1}{27} & \frac{1}{81} & \frac{1}{243} \end{array}

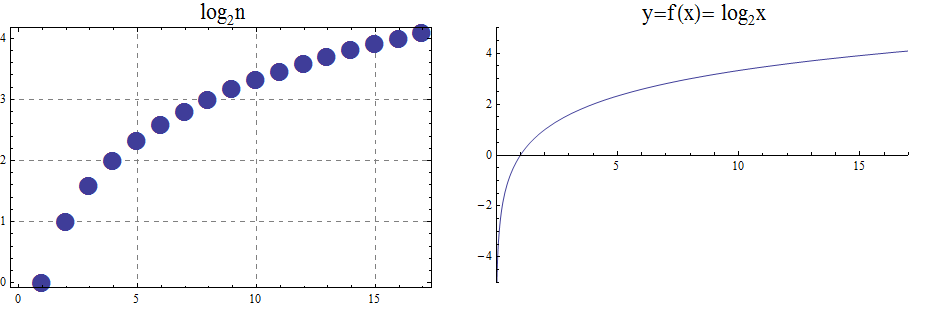

13.4.2. Logarithmic Functions

Logarithmic functions are the inverse functions corresponding to exponential functions and are used to solve exponential equations. For example, \(y=2^x\) is solved for \(x\) by inverting \(x=\log_2{y}\). Properties of logarithms follow from this relationship between exponentials and logarithms and properties of the exponentials.

We summarize three important properties of logarithms.

All other properties of logarithmic functions come from properties relating the logarithm as the inverse of the exponential and the equivalence of the logarithm \(a =\log_b m\) with \(b^a=m\).

When the base \(b\) is greater than 1, the logarithm function is increasing, as in the case \(f(x) = \log_2 x\).

\begin{array}{llllllcccccc} & x & \frac{1}{32} & \frac{1}{16} & \frac{1}{8} & \frac{1}{4} & \frac{1}{2} & 1 & 2 & 4 & 8 & 16 & 32 \\ & log_2 x & -5 & -4 & -3 & -2 & -1 & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \end{array}

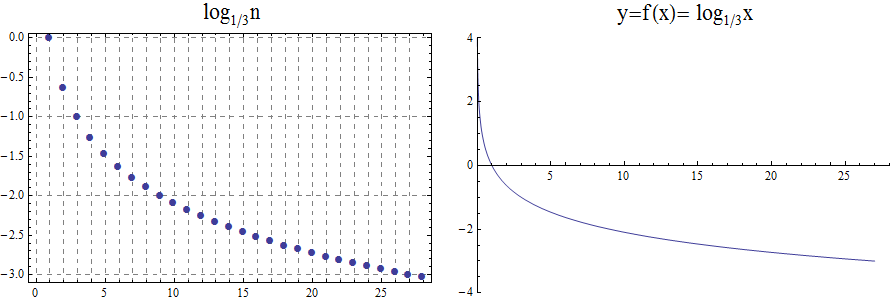

When the base \(b\) is less than 1, the logarithm function is decreasing exponentially, as in the case \(f(x) = \log_{\frac{1}{3}} \ x\).

\begin{array}{llllllcccccl} & x & \frac{1}{243} & \frac{1}{81} & \frac{1}{27} & \frac{1}{9} & \frac{1}{3} & 1 & 3 & 9 & 27 & 81 & 243 \\ & \log_{\frac{1}{3}} x & 5 & 4 & 3 & 2 & 1 & 0 & -1 & -2 & -3 & -4 & -5 \end{array}